Who is responsible for illegal content that appears in the cloud? What is the liability of the provider in case of leakage of sensitive data? When can a customer claim compensation for lost profits? Where does the liability of the cloud provider end and what is the responsibility of the user = customer? These are questions that every cloud service provider faces. The general answer is: Compliance with the relevant business standards and applicable laws is in principle the responsibility of both parties. But what does this mean?

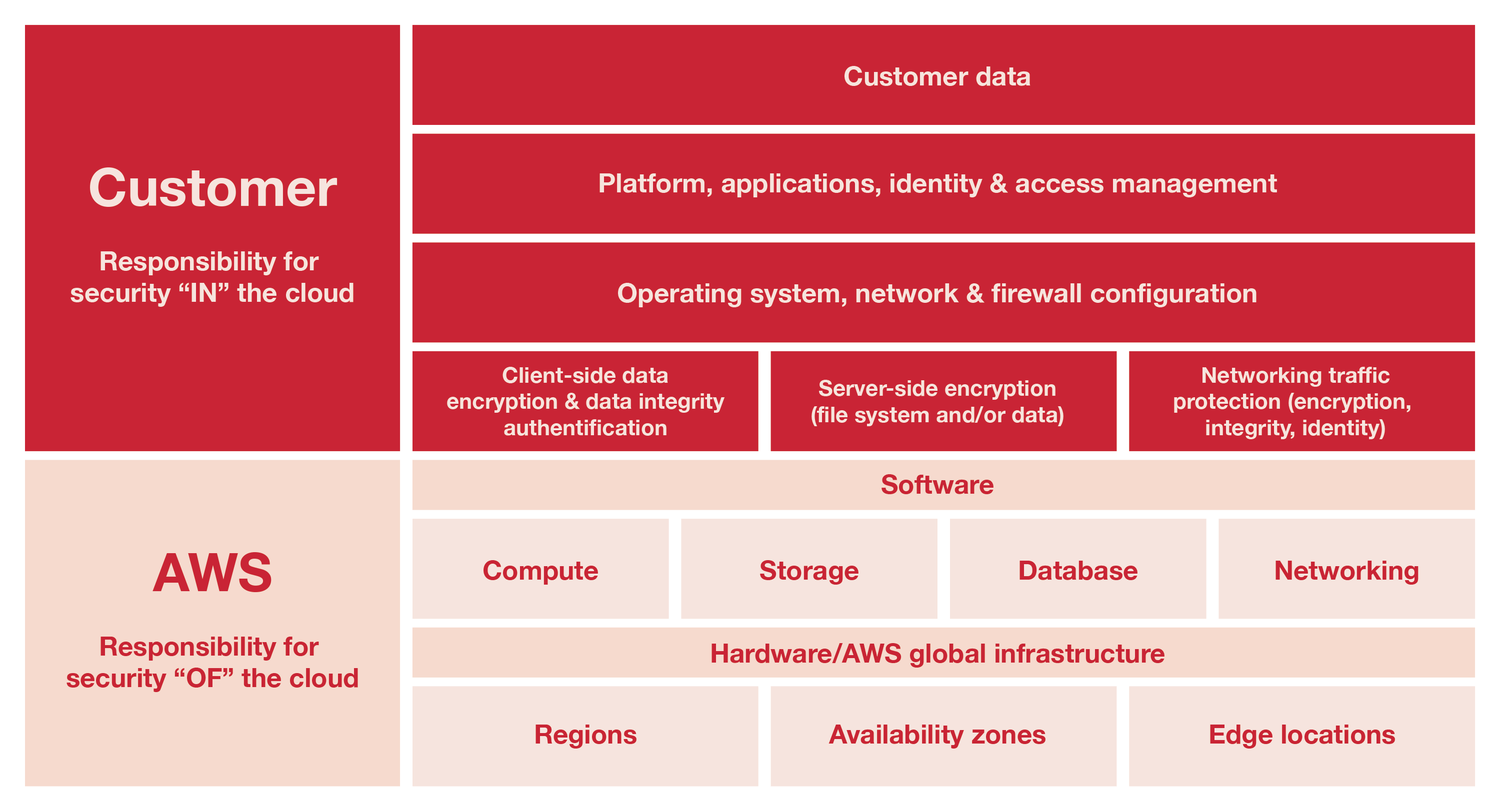

We are talking about the so-called shared responsibility model. A two-party contractual relationship reduces the burden on the customer, as the Cloud Service Provider (CSP) operates, manages and controls the components of the host operating system and virtualization layer, right down to the physical security of the devices on which the cloud service runs. The customer, in turn, assumes responsibility and management of the hosted operating system, including updates and security patches, and other related application software.

This division is referred to as Security OF the Cloud and Security IN the Cloud.

Security OF the Cloud

The CSP is responsible for protecting the infrastructure on which all services run. The infrastructure is composed of the hardware, software, networks and devices on which the cloud services are run.

Security IN the Cloud

The Customer is responsible for the management, content and legality of its data, platforms, applications, the classification of its assets and the adequate use of tools to apply the relevant permissions and access. The exact line of demarcation between customer and CSP responsibility depends mainly on the specific business model chosen (IaaS, PaaS or SaaS).

Who is responsible for illegal content uploaded to the cloud?

Under the so-called shared responsibility model, the customer is solely responsible for the legality of the content. The CSP has no real technical ability to control and influence the content uploaded in the cloud, as it does not have access to the uploaded content under standard circumstances. We consider illegal content to be any files, applications, documents, audio and video, software or other digital items, the possession or creation of copies of which is contrary to the legal regulations governing the contractual relationship between the CSP and the customer. This may include, for example, infringements of intellectual property rights (in particular copyright), personality protection rights or even child pornography.

The express exclusion of liability of CSPs in similar cases is contained in the terms and conditions of probably all relevant CSPs. Such exclusion of CSP liability is also in line with the so-called “mere conduit” exception, regulated by the Slovak E-Commerce Act and the European Directive on Electronic Commerce,[1] which apply to the provision of cloud services[2]. The only exception in this respect is where the CSP has become aware of the illegality of the content stored in the cloud or has been ordered by a court to remove the content. In such cases, even the customer has to answer towards the CSP, especially if the CSP’s reputation or goodwill would be compromised.

[1] See § 6 of Act No. 22/2004 Coll. on Electronic Commerce, as amended. See also Article 12 of Directive 2000/31/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 8 June 2000 on certain legal aspects of information society services in the internal market, in particular electronic commerce (Directive on electronic commerce).

[2] Pursuant to Section 2(1) of Act No. 22/2004 Coll. on Electronic Commerce, an information society service is a service provided remotely during the connection of electronic devices via an electronic communication network, usually for a fee at the request of the recipient of the information society service, in particular commercial communication, processing, transmission, storage, retrieval or collection of data and electronic mail, except for personal electronic mail.

What is the responsibility of the CSP in the event of a security incident involving the leakage of sensitive personal data?

In terms of the GDPR, the customer is in the position of the controller and the cloud provider is in the position of the processor. (This assumption may not always be true, but that is another topic to which we will return later.) The customer is primarily liable to data subjects whose personal data has been leaked as a result of a security incident. A CSP would only be liable, presumably alongside the customer, if it failed to comply with the obligations that the GDPR expressly imposes on processors, or if it acted in excess of or contrary to the customer’s lawful instructions. In practice, this means that if the CSP is properly fulfilling all of the obligations to which it has committed itself in its contract with the customer, its liability will be unlikely as a result of a security incident. In this case, we assume the CSP acted with professional diligence. In the GDPR regime, this is in particular the adoption of appropriate security measures pursuant to Article 32 GDPR.

How is the amount of compensation for cloud usage addressed?

The terms and conditions of probably all relevant CSPs also contain a clause on the so-called limitation of damages. Such limitation (cap) usually represents the aggregate of the contractual fees paid by the injured customer to the CSP for the last 6 or 12 months of using the cloud services. Also under Slovak law (Commercial Code) it is possible to contractually limit the amount of foreseeable damages. However, it should be stressed that this clause only applies where the CSP is actually liable for damages, as the mere fact that the customer did or did not use the cloud does not give rise to any claim by the customer for damages against the CSP.

What about lost profits? Can a customer claim compensation from a CSP for lost profits due to, for example, the inability to use cloud services in the event of a service outage?

In general, lost profits – as the second of the statutory forms of damage in addition to the so-called actual damage – are damages when the injured party has not had a multiplication of property values as a result of the damage event, even though this could have been expected in the regular course of things. Thus, the loss of profit is not manifested by a diminution of the injured party’s assets (loss of assets, as in the case of actual damage), but by a loss of the expected benefit (income). It is not sufficient to show that there is a likelihood of a multiplication of assets, but it must be established that, in the ordinary course of things (but for the wrongful act of the tortfeasor or the harmful event), the injured party could reasonably have expected an increase in his or her assets which did not occur as a result of the tortfeasor’s act (the harmful event).

Even if these conditions are met in the case outlined in the question, the basic condition that the CSP is liable for damages must still be met (as we have already pointed out in our answer to the previous question). Moreover, usually the amount of damages in cloud services is contractually limited and the lost profits of the customer are unlikely to fall within the so-called foreseeable range of potential damages.

A cursory glance at the contractual documentation of the relevant CSPs reveals that a claim for compensation for lost profits is also often explicitly excluded. Of course, the legal limits of permissible exclusions or limitations of liability for damages apply here as well. Under Slovak law, liability for damages, including lost profits, cannot be contractually excluded in advance or left only at a symbolic level. Thus, if all the statutory conditions of liability for damages (including causation, which we have not yet discussed) are met and the customer proves how much money he has lost as a result of the damaging event, e.g. the amount of the specific transactions thus thwarted, it is possible that the eventual decision of the Slovak court would not have to take into account the contractual exclusion of liability for lost profits and the customer would be granted such a claim.

So let’s take a closer look at that causation.

This is a rather complex matter. In legal theory, a causal relationship (causal nexus) is referred to as a direct connection of phenomena (objective connections) in which one phenomenon (the cause) causes another phenomenon (the effect). A causal relationship is one where there is a cause and effect relationship between the harmful event and the damage. If another fact was the cause of the damage, liability for damage does not arise.

The question of causation is not a question of law, but of fact, which can only be resolved in a particular context. The question of the specific nature of the damage (pecuniary loss) for which compensation is claimed is therefore of fundamental importance for the assessment of liability for damages. It is in the relationship between the specific injury suffered by the injured party (if any) and the specific conduct of the tortfeasor (if unlawful) that the causal link is established. In establishing causation, it is necessary to isolate the harm from the general context and to examine which cause caused it. In doing so, it is not the temporal aspect that is decisive, but the factual connection between cause and effect; however, the temporal connection is helpful in assessing the factual connection. In a successive sequence of phenomena, each cause is caused by something (is itself the effect of something), and each effect caused by it becomes the cause of the next phenomenon.

However, liability cannot be made dependent on unlimited causation. For the attribute of causation is the ‘directness’ of the action of the cause on the effect, in which the cause directly (immediately) precedes and produces the effect. The relationship between cause and effect must therefore be direct, immediate, unbroken; it is not enough if it is merely mediated. Consequently, in establishing causation, it is necessary to examine whether, in the complex of facts which are to be taken into account as the (direct) cause of the damage, there is a fact to which the law attaches liability for the damage. Such a view of causation excludes, in particular, any claims for compensation for so-called indirect damage or consequential or derived damage.

Can a CSP somehow absolve itself of liability for damages?

In Slovak commercial law, liability for damages is constructed as objective[1], i.e. no fault (intentional or negligent) is required, as is the case with general liability for damages under the Civil Code[2]. It follows that a CSP will also be liable by default for damages that are not his fault in this sense if they arise from a breach of his obligations (contractual or statutory).

As a general rule, the only way for a CSP to get rid of this strict liability is by so-called liberation based on circumstances precluding liability[3]. Such a circumstance is considered to be a force majeure (vis maior), i.e. an obstacle which has arisen independently of the CSP’s will and prevents him from fulfilling his obligation – if it cannot reasonably be assumed that the CSP could have avoided or overcome the obstacle or its consequences, or that he would have foreseen the obstacle at the time of the creation of the obligation (the conclusion of the contract).

However, liability is not excluded by an obstacle that arose only at the time when the CSP was in default of its obligation or arose from its economic circumstances (e.g. bankruptcy). The law limits the effects excluding liability to the duration of the obstacle to which the effects are linked. Strict liability certainly does not mean absolute liability. Therefore, sophisticated hacking attacks against otherwise adequately prepared and prudent CSPs may – taking into account all the circumstances of the particular case – fall under force majeure and thus exclude the CSP’s legal liability towards its customers. Of course, reputational damage on the part of the CSP as a direct consequence of the disclosure of the consequences of a hacking attack cannot be excluded in this way.

Similarly, we see the situation through the lens of the GDPR, which also exempts both the controller and the processor from liability for damages in cases where it is proven that they bear no responsibility for the event that caused it[4]. There is currently a ‘preliminary ruling’[5] pending before the CJEU which should answer, among other things, the question of whether a hacking attack is such an event.

[1] See Sections 373 and 757 of Act No. 513/1991 Coll., Commercial Code, as amended.

[2] See § 420 et seq. of Act No. 40/1964 Coll., Civil Code, as amended.

[3] See § 374 et seq. of Act No. 513/1991 Coll., Commercial Code, as amended.

[4] See Article 82(3) GDPR.

[5] See the summary of the reference for a preliminary ruling in Case C-379/08 Reference for a preliminary ruling from the Court of Justice of the European Communities (OHIM) .

Is the CSP insured in case the customer suffers damage?

CSPs are normally insured in case they would be liable for the damage caused. The injured party can then use the insurance benefit to compensate for the damage caused by the insured event.

Why prefer a CSP that is subject to the legislation of the Slovak Republic?

It is always more advantageous and easier for a Slovak customer if the jurisdiction and competence of a Slovak court is established rather than that of a court abroad. It is also more advantageous for the Slovak customer if the contract is governed by Slovak law and not by foreign law (e.g. the laws of the State of California, etc.). Thus, from the point of view of the Slovak customer’s interest, it is mainly a practical question of enforceability of its rights, which may be more complicated in relation to a CSP that is not established, i.e. not domiciled in Slovakia.